In this post I will look at the two earlier songs: "Send Me a Dream" (1912) and "Only of Thee and Me" (1914).

"Send Me a Dream" has an unusually large number of direct and "almost direct" resolutions of the dominant major-ninth chord. Here are two near the beginning. Neither ninth resolves by step, but both chords are clearly independent harmonies acting as V9s in context. Note that the second chord is inverted.

The situation is less clear a few bars later. In the dotted box is a harmony better heard as Eb: viiø7/V. I have made the second box solid but its identity as a ninth is only slightly improved, as the voice's F5 could still be heard as an appoggiatura.

At bar 44 is another instance of a clearly defined secondary V9.

And here are even more just a few bars later.

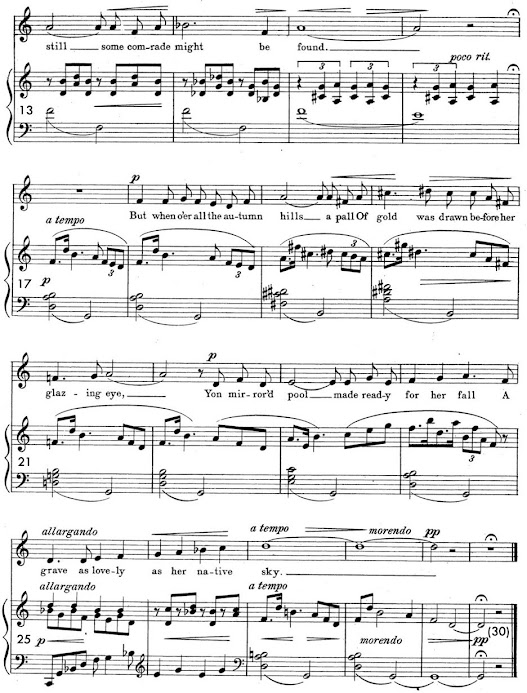

The climax chord (bars 67-68) is a V9 with more iterations of the ninth than I have seen anywhere else to date. At bar 72 is the chord from bar 12, now in root position, and as a surprise G9 appears in the final bars without function, as part of a coloristic wedge figure.By comparison, "Only of Thee and Me" has just one point of interest, and it's a dominant 7th with raised 5th that only becomes a ninth chord (still with raised 5th) when the voice puts in a "throw-away" note D5. The first time (end of the first verse) D5 disappears for sake of A4; the second time (third verse and ending) it acts as ^6 resolving upward to ^8.

|