In 1915, Reynaldo Hahn set poems for children by Robert Louis Stevenson in the Five Little Songs (5 petites chansons). The cycle was first performed and published in 1916. The first song, "The Swing" [La Balançoire], is the subject here.

"The Swing" belongs to a very select group of published compositions in which the major dominant-ninth chord is essential to sound and affect. These include Marion Bauer's "The Epitaph of a Butterfly" (link to my post), Charles Griffes' "The White Peacock" (check this blog post for an abstract and link to my essay: 2020 June 5), and of course the "Russian Dance" from Stravinsky's Petrushka, which I wrote about in the previous post to this blog.

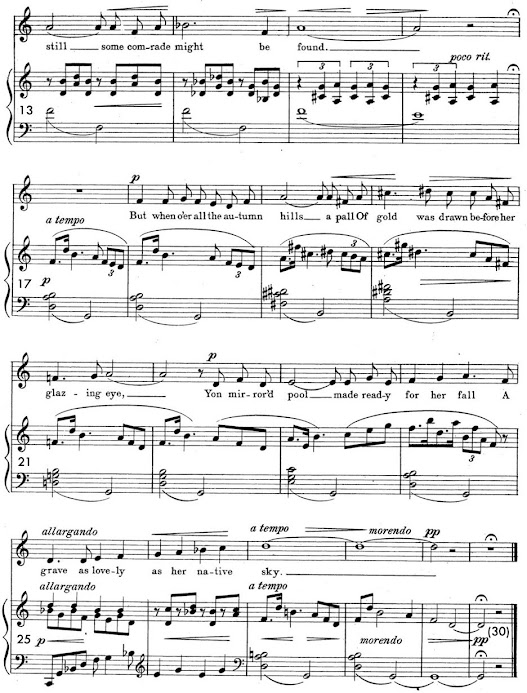

The evocative accompaniment figure in bar 1 is repeated, with slightly shifting harmonies, in all 35 bars, excepting an abbreviated form in bars 32-33. Since the pedal will certainly be held down through each beat, the initial--and frequently repeated--tonic, which I have labeled "I" is just as easily heard as Iadd6. The V11 (or V9sus4) of the second beat "relaxes" into a clear V9 by bar 2, beat 2. In context, the notated Fnat4 in bar 3 sounds like a neighboring E#4 (so G-F#-E#-F# in bars 1-4), but the pitch as Fnat4 will play a role later. The G-F#-E#-F# motion, of course, adds a slightly longer-range swinging figure to the mix.

The poem is in three verses. Each is set slightly differently. Here is verse 1. The letter above each bar indicates the accompaniment figure, as they were labeled in the example above.

Note above that figure C--not figure A or B--appears in the first three bars of this verse. From this point, new twists on the harmony show up in each bar--see below, the score for the second line to the end of the verse. Now the Fnat4 of figure C signals a turn toward IV, which in turn leads quickly to the closing cadence, where the V is again a clear V9.

The piano's brief coda brings a small but interesting play on the ancient post-cadence turn toward IV. In bar 33, Fnat4 hints at a repeat of bars 25ff. and it does go down to E4, but not over IV: instead it's over I to make Iadd6. The arpeggios to prominent E5 and E6 (arrows) are a delightful (but still safe) "swing" just past the tonic triad.