The Radetzky March, op. 228 (1848), is the most well-known composition of Johann Strauss, sr. I am including it here partly for that reason, but partly also to begin making the point that there were repertoires other than the waltz in which the dominant ninth made inroads. Granted, these other repertoires--especially the polka--were directly influenced by the waltz practices of the 1820s and 1830s.

In general, marches were treated more traditionally than dance genres and the dominant ninth is relatively rare in them, but the Radetzky March, especially at the fast tempo it is usually heard today, is loosely aligned in its figures and expression with the galop, and figures from dance or theatrical music play a major role.

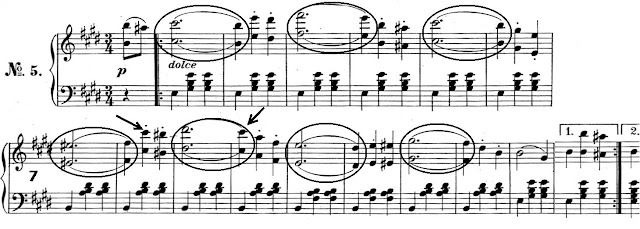

Note the parallelism of ^6-^5 over V then over I in the first strain (bars 5-6).

In the trio, we hear two direct resolutions of the ninth: see the arrows in the examples below:

First strain:

Second strain:

Monday, December 31, 2018

Monday, December 24, 2018

Others, circa 1800-1850

Carl Czerny, 100 Progressive Recreations (alternate titles: Erster Clavier-Unterricht in 100 Unterholungen; 100 Recréations) is unusual for Czerny in that it was not assigned an opus number and the date of first publication is uncertain (at least, I can't find one easily). Also, somewhat unusually, the majority of the 100 pieces are simplified versions of familiar melodies or excerpts from larger compositions, as with Bellini's Norma in this case. This example is interesting for the suspension figure that begins with the dramatically emphasized and positioned ^6. The whole figure fits my category 1.3 best, even though the ninth is not attacked again on the strong beat.

Auber, Die Muette de Portici, n24 "Honneur" theme. Also in category 1.3 (arrow, second system third bar), but in 1.2 (arrow, second system sixth bar), the difference being that the latter is sounded on a weak beat.

Donizetti in Czerny, 100 Recreations. Category 1.3 in bar 7 (D6 on the strong beat resolves to C6 within the dominant harmony). In bars 3-4, however, I am wary of the 32nd note C6. If that is a resolution, then category 1.3 holds, but I prefer 2.1, an indirect resolution of ^6 to ^5 over the tonic chord, and therefore bar 3 is a proper dominant ninth chord.

Donizetti, Princess Helena's Polka, as arranged by Allen Dodworth (New York, 1847). The modern notation is by Robert A. Hudson. A clear V9 harmony with the uncommon rising resolution.

Rossini from La Cenerentola, in Czerny 100 Recreations. A simple emphasized upper neighbor/appoggiatura, immediately resolved within the V chord.

William Schubert, arranger, Three Favorite Polkas (Philadelphia, 1845), n1. Indirect resolution of the ninth to the fifth of the tonic chord, category 2.1.

Allen Dodworth, Very Best Polka (New York, 1850). The modern notation is by Robert A. Hudson. As above, indirect resolution (category 2.1). In bars 6-8, ^5 is easily imagined given the earlier figure in bars 2-4.

Henri Appy, Elizabeth Polka. Published in St. Louis in 1853. Direct (or very quick indirect) resolution (boxed). An ascending cadence gesture in bars 7-8.

W. P. Badger, Pascagoula Melodies n1: Union Polka (Boston, 1853). Direct resolution in the boxes.

Ferdinand Beyer, Trois Polkas, op 51, n1: Camellia Polka (Mainz, 1846?).

Auber, Die Muette de Portici, n24 "Honneur" theme. Also in category 1.3 (arrow, second system third bar), but in 1.2 (arrow, second system sixth bar), the difference being that the latter is sounded on a weak beat.

Donizetti in Czerny, 100 Recreations. Category 1.3 in bar 7 (D6 on the strong beat resolves to C6 within the dominant harmony). In bars 3-4, however, I am wary of the 32nd note C6. If that is a resolution, then category 1.3 holds, but I prefer 2.1, an indirect resolution of ^6 to ^5 over the tonic chord, and therefore bar 3 is a proper dominant ninth chord.

Donizetti, Princess Helena's Polka, as arranged by Allen Dodworth (New York, 1847). The modern notation is by Robert A. Hudson. A clear V9 harmony with the uncommon rising resolution.

Rossini from La Cenerentola, in Czerny 100 Recreations. A simple emphasized upper neighbor/appoggiatura, immediately resolved within the V chord.

William Schubert, arranger, Three Favorite Polkas (Philadelphia, 1845), n1. Indirect resolution of the ninth to the fifth of the tonic chord, category 2.1.

Allen Dodworth, Very Best Polka (New York, 1850). The modern notation is by Robert A. Hudson. As above, indirect resolution (category 2.1). In bars 6-8, ^5 is easily imagined given the earlier figure in bars 2-4.

Henri Appy, Elizabeth Polka. Published in St. Louis in 1853. Direct (or very quick indirect) resolution (boxed). An ascending cadence gesture in bars 7-8.

W. P. Badger, Pascagoula Melodies n1: Union Polka (Boston, 1853). Direct resolution in the boxes.

Ferdinand Beyer, Trois Polkas, op 51, n1: Camellia Polka (Mainz, 1846?).

Monday, December 17, 2018

Mozart

Mozart, always keenly aware of music for dancing, held an appointment during the last three years of his life as a composer of dance music for the Imperial court. Among these works are three sets of German Dances, K600, 605, and 606. In none of them does he write a properly functional dominant ninth harmony (that is one with a direct or indirect resolution of ^6 to ^5 in the following tonic), but his treatment of scale degree ^6 is worth some attention. Two additional examples come from late sets of menuets, K568 & 599.

German Dances, K600n2, trio. We've seen this in earlier posts on Theodor Lachner and Josef Lanner: the clichéd 18th century cadence with ii6 as harmonization of a figure emphasizing ^6. It was the simplified harmonies of the Laendler tradition (without the ii6) that led to a distinct dominant ninth harmony, but we can see here that the melodic figure was already well established in concert music (or formal music for dance), too.

K600n3, trio, first strain. What I would call the "other" way to treat harmony below ^6 before the nineteenth century: as viiø7.

K600n3, trio, second strain. The double positioning of ^6 in parallel figures over tonic and dominant is straight out of the Laendler repertoire.

German Dances, K606n1. Attention to the same ^6-^5 figure but only over I. This is one of the closest imitations of the Laendler style in Mozart's music (there are others!).

Menuets, K568n1. Even in the menuets one can sometimes hear the ascending drive across a strain toward an expressive ^6 (circled), but note that Mozart uses IV in the bass.

Menuets, K599n12, trio. The figures in bars 3, 5, and 6 belong to the menuet repertoire and predate 1790 by several decades. The point of interest is the piccolo in bar 7: once again a gradual, persistent rise across the strain toward an expressive ^6 but this time it is firmly over V and on the beat. The sound of bar 7, then, is certainly that of the dominant ninth chord, even if we cannot really apply the label to the harmony.

German Dances, K600n2, trio. We've seen this in earlier posts on Theodor Lachner and Josef Lanner: the clichéd 18th century cadence with ii6 as harmonization of a figure emphasizing ^6. It was the simplified harmonies of the Laendler tradition (without the ii6) that led to a distinct dominant ninth harmony, but we can see here that the melodic figure was already well established in concert music (or formal music for dance), too.

K600n3, trio, first strain. What I would call the "other" way to treat harmony below ^6 before the nineteenth century: as viiø7.

K600n3, trio, second strain. The double positioning of ^6 in parallel figures over tonic and dominant is straight out of the Laendler repertoire.

German Dances, K606n1. Attention to the same ^6-^5 figure but only over I. This is one of the closest imitations of the Laendler style in Mozart's music (there are others!).

Menuets, K568n1. Even in the menuets one can sometimes hear the ascending drive across a strain toward an expressive ^6 (circled), but note that Mozart uses IV in the bass.

Menuets, K599n12, trio. The figures in bars 3, 5, and 6 belong to the menuet repertoire and predate 1790 by several decades. The point of interest is the piccolo in bar 7: once again a gradual, persistent rise across the strain toward an expressive ^6 but this time it is firmly over V and on the beat. The sound of bar 7, then, is certainly that of the dominant ninth chord, even if we cannot really apply the label to the harmony.

Monday, December 10, 2018

Johann Strauss, sr.

Johann Strauss, sr.—also called Johann Strauss I in the literature—was an excellent violinist who started playing professionally under Michael Pamer, the most important connection between the earlier waltz and Laendler traditions and urban practices after about 1820. Strauss then played under Josef Lanner, but soon formed his own band (in 1825) and enjoyed immediate success. The pieces below come from the last two years of his life; he died in 1849.

Strauss, sr. Damen Souvenir Polka, op236, second strain. An indirect—actually very nearly direct—resolution, thus either category 2.1 or 2.4 depending on how you hear it.

Strauss, sr., Die Sorgenbrecher Walzer, op230n2. Here Strauss puts such emphasis on E6, as the ninth, that it is not hard to imagine we hear a D6 over the subsequent tonic.

The remaining examples are also direct resolutions to the tonic (my category 2.3).

Strauss, sr., Wiener Kreuze Polka, op220

Strauss, sr., op236, first strain

Strauss, sr., Exeter Polka, op249 2trio

Strauss, sr., Die Adepten Walzer, op216n5

Strauss, sr. Damen Souvenir Polka, op236, second strain. An indirect—actually very nearly direct—resolution, thus either category 2.1 or 2.4 depending on how you hear it.

Strauss, sr., Die Sorgenbrecher Walzer, op230n2. Here Strauss puts such emphasis on E6, as the ninth, that it is not hard to imagine we hear a D6 over the subsequent tonic.

The remaining examples are also direct resolutions to the tonic (my category 2.3).

Strauss, sr., Wiener Kreuze Polka, op220

Strauss, sr., op236, first strain

Strauss, sr., Exeter Polka, op249 2trio

Strauss, sr., Die Adepten Walzer, op216n5

Monday, December 3, 2018

Josef Lanner

Josef Lanner is the one contemporary about whom we can be confident that he influenced Schubert's own waltz improvisation and composition. We know that Schubert heard Lanner’s orchestra in live performance, probably on multiple occasions and while Johann Strauss, sr., was still a member of the band.

Lanner, Trennungs-Walzer (1828), op19_n5, first strain. A curiously reversed resolution in bars 9-10. The circles throughout the strain show the overwhelming dissonance-resolution motive. In bars 9-10, however, the third of the underlying chord (D#5/D#6) is resolved to the ninth C#5/C#6!

Lanner, Flora-Walzer, op33_n4, first strain. Scale degree ^6 is a melodic element in each instance.

Lanner, Redout-Carneval-Tänze (second set; 1830), op42_n5, first strain. Similar to op19n5 in its motive, but now there is no "mistake" about the resolution of ^6.

Lanner, op19_n2. As in the previous example.

Lanner, op33_n4, second strain. Similar to one of the examples from Schubert in its sustained drive upwards culminating on the highly expressive ^6 as the ninth of the dominant.

Lanner, op42_n6. Three different treatments of the ninth, at (a), (b), and (c).

The remaining examples are all direct resolutions, that is, the ninth resolves not within the dominant but in the following tonic.

Lanner, op33_n5.

Lanner, op42_n5, second strain

Lanner, Alpen-Rosen Walzer (1842), op162 n3

Lanner, op162 n4

Lanner, Die Romantiker (1842), op167 n4

Lanner, Trennungs-Walzer (1828), op19_n5, first strain. A curiously reversed resolution in bars 9-10. The circles throughout the strain show the overwhelming dissonance-resolution motive. In bars 9-10, however, the third of the underlying chord (D#5/D#6) is resolved to the ninth C#5/C#6!

Lanner, Flora-Walzer, op33_n4, first strain. Scale degree ^6 is a melodic element in each instance.

Lanner, Redout-Carneval-Tänze (second set; 1830), op42_n5, first strain. Similar to op19n5 in its motive, but now there is no "mistake" about the resolution of ^6.

Lanner, op19_n2. As in the previous example.

Lanner, op33_n4, second strain. Similar to one of the examples from Schubert in its sustained drive upwards culminating on the highly expressive ^6 as the ninth of the dominant.

Lanner, op42_n6. Three different treatments of the ninth, at (a), (b), and (c).

The remaining examples are all direct resolutions, that is, the ninth resolves not within the dominant but in the following tonic.

Lanner, op33_n5.

Lanner, op42_n5, second strain

Lanner, Alpen-Rosen Walzer (1842), op162 n3

Lanner, op162 n4

Lanner, Die Romantiker (1842), op167 n4

Monday, November 26, 2018

Schubert, part 2

This continues last week's post with further examples of the treatment of ^6 and the dominant ninth harmony in Schubert's waltz collections, D365 (1821) and D779 (1825).

D779n30. The ninth first appears in the pickup to bar 5, then is repeated as part of a simple arpeggio (notably without ^7) and is easily heard to resolve as ^6-^5 over I in bar 6.

D365_n12. We hear V9 unequivocally in bar 2, but there is no ^5 in bar 3 (we would have to imagine it). But there is no doubt in bars 6-7, where the figure is repeated an octave higher and the ninth resolves on the strong beat of bar 7. Note that the second inversion of I counts as a harmony for resolution of the ninth -- Schubert was quite fond of dominant pedal points, especially in his early Laendler, and he put all sorts of melodic figures above them.

D779n17. A textbook case of a true V9 harmony resolving directly, with a 6-5 figure over I.

D779n2. Almost identical to the preceding, except that the V9 is more strongly defined.

D365_n30. Like the above, and repeated on the dominant level at the beginning of the second strain.

D779n20. Like the above.

D779n30. The ninth first appears in the pickup to bar 5, then is repeated as part of a simple arpeggio (notably without ^7) and is easily heard to resolve as ^6-^5 over I in bar 6.

D365_n12. We hear V9 unequivocally in bar 2, but there is no ^5 in bar 3 (we would have to imagine it). But there is no doubt in bars 6-7, where the figure is repeated an octave higher and the ninth resolves on the strong beat of bar 7. Note that the second inversion of I counts as a harmony for resolution of the ninth -- Schubert was quite fond of dominant pedal points, especially in his early Laendler, and he put all sorts of melodic figures above them.

D779n17. A textbook case of a true V9 harmony resolving directly, with a 6-5 figure over I.

D779n2. Almost identical to the preceding, except that the V9 is more strongly defined.

D365_n30. Like the above, and repeated on the dominant level at the beginning of the second strain.

D779n20. Like the above.

Monday, November 19, 2018

A Gallery of Simple Examples of the Dominant Ninth

I have published an essay titled Dominant Ninth Harmonies in the 19th Century: A Gallery of Simple Examples Drawn from the Dance and Theater Repertoires: link to the essay.

Here is the abstract:

Here is the abstract:

In European music, freer treatment of the sixth and seventh scale degrees in the major key encouraged the use of independent V9 chords, which appear already early in the nineteenth century, are common by the mid-1830s, and are important to the process by which the hegemony of eighteenth-century compositional, improvisational, and pedagogical practices were broken down. This essay provides multiple examples of the clearest instances of the V9 as a harmony in direct and indirect resolutions.

Schubert, part 1

In an earlier post, I observed that "one can easily find all seven types of the dominant ninth in the waltzes of Schubert alone." Schubert, therefore, deserves to be an early entry in the repertoire documentation that is the main goal of this blog. The examples below are drawn from the Original-Tänze, D365, and the Valses sentimentales, D779. Both are miscellaneous collections of dances, D365 published in 1821, and D779 in 1825. Most have their origins in music improvised for social dancing. The dances are in both Deutscher (German dance) and Laendler style--sometimes both in the different strains of the same piece. The Laendler style dominates in D365, whereas D779 is much more mixed.

This is n3 in the Valses sentimentales, D779 (1825). Apologies for all the boxes—the examples for D365 come from an essay of mine on the sixth scale degree, Scale Degree ^6 in the 19th Century: Ländler and Waltzes from Schubert to Herbert (link). Here the impetus to ascent is as strong as it could be. A direct resolution within V in bar 5 is followed by a remarkable "one note too far" at the end of the long ascent over the strain.

D779n3, second strain. The ^6 in bar 7 (arrow) is somewhat like the preceding—an expressive element within the V harmony—but without the dramatic emphasis, to be sure. The question marks over B5 in bars 1 and 5 indicate the uncertain status of that note: on beat 1, is it a ninth; or is it part of a complicated neighbor figure; or is it a ninth that resolves within the chord to A5 on beat 3? Any of those explanations is plausible.

D365n13:

D779n2: Once again the ninth receives attention: E5 is on the downbeat of bar 3. It resolves immediately to D5. The fourth note in the bar, another E5, is a simple escape tone.

This is the second strain of D779, n14. Despite its resolutions into the underlying V7 chord in bars 6-7, the ninth is an essential element of the sound of these two bars.

D365n2, the best known of Schubert's waltzes in the 1820s and for several decades thereafter. Similarly to the preceding examples, F5 in bars 5 and 7 resolves within the V harmony but is given strong melodic emphasis that lingers as part of the sound. The figure also mimics earlier accented notes--see the various circled notes.

D365n31. What was said just above--about lingering as part of the sound--is even more true here, where Schubert gives emphatic attention to the V9 sound in bars 2 & 6 (boxed) and also to ^6 above I in bar 4.

Post continues on Monday next week.

This is n3 in the Valses sentimentales, D779 (1825). Apologies for all the boxes—the examples for D365 come from an essay of mine on the sixth scale degree, Scale Degree ^6 in the 19th Century: Ländler and Waltzes from Schubert to Herbert (link). Here the impetus to ascent is as strong as it could be. A direct resolution within V in bar 5 is followed by a remarkable "one note too far" at the end of the long ascent over the strain.

D779n3, second strain. The ^6 in bar 7 (arrow) is somewhat like the preceding—an expressive element within the V harmony—but without the dramatic emphasis, to be sure. The question marks over B5 in bars 1 and 5 indicate the uncertain status of that note: on beat 1, is it a ninth; or is it part of a complicated neighbor figure; or is it a ninth that resolves within the chord to A5 on beat 3? Any of those explanations is plausible.

D365n13:

D779n2: Once again the ninth receives attention: E5 is on the downbeat of bar 3. It resolves immediately to D5. The fourth note in the bar, another E5, is a simple escape tone.

This is the second strain of D779, n14. Despite its resolutions into the underlying V7 chord in bars 6-7, the ninth is an essential element of the sound of these two bars.

D365n2, the best known of Schubert's waltzes in the 1820s and for several decades thereafter. Similarly to the preceding examples, F5 in bars 5 and 7 resolves within the V harmony but is given strong melodic emphasis that lingers as part of the sound. The figure also mimics earlier accented notes--see the various circled notes.

D365n31. What was said just above--about lingering as part of the sound--is even more true here, where Schubert gives emphatic attention to the V9 sound in bars 2 & 6 (boxed) and also to ^6 above I in bar 4.

Post continues on Monday next week.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)