Discussion of inversions of the major dominant ninth chord typically stall on Arnold Schoenberg's famous needling of detractors about a fourth inversion chord in his Verklärte Nacht (see my post on several authors' analyses of the passage: link). But now that I am done with that ritual notice, let's move on.

Looking at examples from posts to this blog and from essays published on the TexasScholarworks platform, I found 25 instances, considerably more than I expected, though as we will see I have included a particular type that some readers may not accept as a proper inversion. The numbers were: first inversion 5; second inversion 17; third inversion 2; fourth inversion a questionable 1.

In the graphic below, I have shown G7 and inversions with simple voicing, then the same for G9, whose inversions are labeled a-d.

The figure at (b4) is of course a schematic form of the ubiquitous oom-pah bass. Its resolution nicely balances line and bass function; Schenkerians often represent this as shown below.

The third inversion--at (c1) and (c2)--has the smoothest voiceleading of the lot, with a pleasant pair of tenths between the bass and the voice carrying the ninth. At (d1) the fourth inversion collapses into V7; (d2) shows that this inversion leads to I6/4, (d3) that one can avoid the 6/4 with a mediant, but iii is the weakest of the major key's three minor triads and to make things worse is often used functionally as a dominant, which would make the ninth chord resolve internally.We begin with the first inversion. Here is an excerpt from the third waltz in Johann Strauss, jr.'s Künstlerleben [Artist's Life], op. 316:

And here is nearly the same in the trio from his father's Damen-Souvenir Polka, op. 236:Again from Strauss Vater, in the trio of his best-known piece, the Radetzky March:My added unfolding symbols give you the essence of the "particular type": it is ^5 (E2) that moves directly to ^1 (A2) in the bass, but ^7 (G#2) is given such emphasis that it will still be heard as resolving to ^8 (A2). The balance between line and function is perfect.

A march by Sousa, "The White Plume":

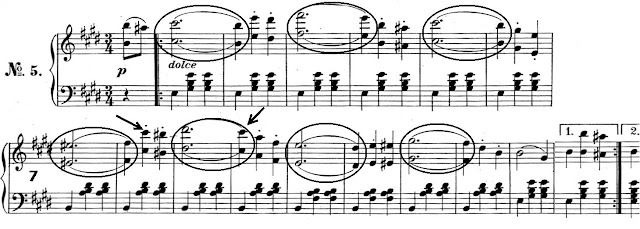

And finally another from Johann Strauss, sr., the second strain of the second number from Die Sorgenbrecher, op. 230, the most often played (or, at least, recorded) of his waltzes: