I have added Vincent Persichetti's classic Twentieth Century Harmony: Creative Aspects and Practice to this series of posts, first, because it is in a traditional textbook format and uses a traditional sequence, despite the very different material being discussed, and, second, because it is a good representative (still cited today) of mid-20th century attitudes toward harmony and harmony pedagogy among then-practicing North American and European composers.

Like other texts that tackled complex harmony beginning already in the early 20th century, Twentieth Century Harmony also stands in the awkward position of prescribing harmonic solutions at a time when harmonic function was quickly losing its hegemonic force. Persichetti's claim isn't small: The book is "a detailed study of the essential harmonic technique of the twentieth century, presented according to the practice of contemporary composers. This text aims to define this harmonic activity and make it available to the student and young composer."

The magnitude of the problem--and of Persichetti's optimism--is apparent in the opening of chapter 1:

Any tone can succeed any other tone, any tone can sound simultaneously with any other tone or tones, and any group of tones can be followed by any other group of tones, just as any degree of tension or nuance can occur in any medium under any kind of stress or duration. Successful projection will depend upon the contextual and formal conditions that prevail, and upon the skill and the soul of the composer.

It's hard to know what to expect of ninth chords, given those assertions. But under the circumstances, the general statement seems straightforward enough, though it certainly requires the information and examples that follow to be saved from vagueness and to offer any kind of practical instruction:

The seventh and ninth members of chords are traditionally dissonant tones but they have been freed of some of their former restrictions. These chords have become stable entities in themselves with their dissonant tones not necessarily prepared or resolved. Seventh and ninth chords, like triads, may progress within or outside any scale formation, original or traditional. Under certain formal conditions the seventh and ninth are treated as dissonant tones needing resolution; but as independent seventh and ninth chords they have the facility of triads.

A problem common to related literature is the definition of chords. Ninth chords have five members and can be considered complex. As we saw with Sessions, inversions can introduce considerable ambiguity about chordal identity. Persichetti says fourth inversions are used freely, and one example offers an opening chord of A2-G3-F4-B4 as G9. I have trouble hearing this as anything other than Am9, despite the "extraneous" F4. (Hindemith, btw, would agree with Persichetti, as the strongest interval by his calculation is the third G-B.)

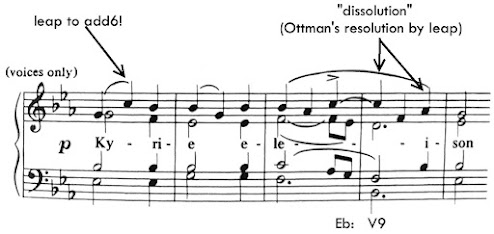

Much the same with non-harmonic notes. Here is the beginning of one example with my annotations:

Finally, after all this, there isn't much to say that connects to the topic of this blog, because--as the example above hints--Persichetti greatly favors other seventh and ninth chord types over the major dominant ninth, which does appear in a reference example of the same kind of sequential progression that we saw in Mitchell and Ottman, but only once in the chapter's nine composed examples.