This may be a good moment to pause the survey of treatises and textbooks in order to make a few observations of a more general kind and to restate the goal of the survey and, beyond that, the goal of this blog.

There is a progressive historical narrative to be told, but it is not one of smooth, incremental movement from triads and seventh chords (18th century) through triads with added 6ths and ninth chords (1850?) to elevenths, thirteenths, and even more complex harmonic structures (1890? 1900?). One does find such narratives even in textbooks beginning in mid-century, but "histories of harmony" become much more common later, when history became an important cultural idea. The extended tertian chord model—stacking thirds—was particularly amenable to such accounts. As Damian Blättler describes it: "The fact that the model’s chord types can be arranged in sequence —triads are followed by seventh chords, seventh chords by ninth chords, and so on—has been used both as a pedagogical sequence and as a narrative about the development of chord types" (2013, 6). In a footnote Blättler offers an example:

A particularly clear-cut narrative claim is made by Alfredo Casella: "[Jean Marnold once said that the only musical difference between romanticism and the 18th century dwindled down to a single chord: the dominant major ninth. There is much truth in this, even though it seems to reduce a century of music to a purely technical problem.] Assuredly the chord of the major ninth, introduced by Weber, gave a totally different complexion to the entire musical language of the 19th century. Nor is it less evident that the exploitation of this chord reaches its culminating point in Debussy. . . . The following harmonic concept [the augmented 11th chord], . . . it is only in Ravel that the new chord is finally used in a constant, conscious, and spontaneous manner.” [the section at the beginning of the quote was added from the original publication to broaden the context]

The ninth, however, was already among the figures that continuo players needed to learn in the late 17th century, and when early 18th century writers tried to gain control of the large catalogue of figures, the ninth came along, too. In practice, the common figures of the ninth were relatively few:

(It is important to remember that these are figures designed for musical practice, not theoretical categories. Thus, 9-8 might mean 9-8 over 3 as in (1) above in one city, but it might mean 9-8 over 4-3 as in (2) in another city or region; it might also mean either (1) or (2) in still a third city or region, the continuo keyboard player being expected to make an appropriate choice according to the circumstance.)

All of these we would understand as linear formations (probably suspensions, but also appoggiaturas or accented neighbor notes), but Rameau essentially "invented" the dominant ninth as a harmony, first through his elevation of the status of the dominant, then through his notion of

supposition and the subsequent reverse strategy of stacking thirds. Because of his influence, (almost) everyone after him accepted the ninth chord as a harmonic entity (recall, for example, that it is among the eight basic chords in Catel's

Traité:

link). Thus the ninth chord was not "introduced by Weber"—it was a theoretically accepted harmony, but one without any real presence in practice (according to the treatise authors).

In fact, thanks to the exploitation of ^6 in the major key, as Jeremy Day-O'Connell has documented, the dominant ninth harmony—in its characteristically complex position as sometimes linear, sometimes harmonic—was already a part of musical practice no later than 1820, especially in music for dance. Here, as a reminder, are several examples from Schubert. (At least some of these were not presented in previous posts or in essays published on Texas ScholarWorks.) I looked at his last published set, the

Valses nobles, D. 969, generally regarded as intended more for performance than as accompaniment for dancing. In no. 11, at (a), is a direct resolution. At (b), note the parallel treatment of V7, and at (c) the realization of the ascent through the upper tetrachord, G5-C6, that was encouraged by freer—and this case expressively and structurally significant—treatment of ^6.

In no. 2, a plainly audible indirect resolution with unfolded thirds: F#5 to E5, D5 to C#5. In the cadence the figure encourages an open ending (IAC, not PAC, with the melody on ^3).

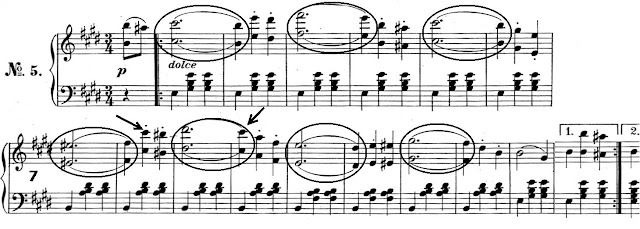

In no. 5, another parallel treatment of the type most common in the waltz throughout the century: ^6-^5 over the dominant (bar 9), then ^6-^5 over the tonic (bar 11). Here the ninth is resolved internally, and the chord in bar 9 has to be regarded as an inversion of V7.

In no. 1, at (a), the internal resolution is stretched over three bars (A5 in bars 4-5 to G5 in bar 7). As in no. 11, the upper tetrachord remains important: in the cycle of fifths sequence at (b), then in the dramatic rising cadence at (c).

In no. 4, the urge toward the upper register is treated a bit differently. At (a), an accented ^6 resolves internally, and within the bar, is repeated, then repeated again as the dominant in the cadence (bar 7). The design is a small ternary form. In the reprise, At (b), the same figure, but then carried up to the instrument's highest octave to end—at (c).

Finally, in no. 10, ^6 is an essential expressive element, but its harmonic expression is vi (in bars 4 and 12), not V9.

The dominant ninth chord as a harmony finds it way into the theatre indirectly through the dance (especially in waltz numbers) and becomes a cliché by the time of Offenbach's great successes beginning with

Orfée aux Enfers (1858) and continuing through the 1860s, but we should also point to its prominent appearance in the first act of Wagner's

Lohengrin (1854) and in the Prelude to Act II of

Tannhäuser (1860). For the latter I presented the passage below in this post:

link.

This idea of intensification of the major dominant seventh at climax points or in cadences persisted through the rest of the century and beyond, as did ^6 with both V9 and Iadd6 in music of pastoral, lyrical, or sentimental character. (In the dance and concert dance repertoire, the history of the dominant ninth is bound up with a remarkably free treatment of the scale's upper tetrachord.) Only in the 1890s did color and harmony-as-function reach parity in concert musics, and in this sense Casella was right that "exploitation of this chord reaches its culminating point in Debussy."

I do not expect any grand new revelations to emerge from the roughly twenty additional textbooks/treatises still to be surveyed and discussed in this blog. The idea is to fill out and complete the documentation, but I will be looking for additional repertoire examples, which will of course serve the main goal of the blog as originally stated.

Reference:

Damian Blättler, "A Voicing-Centered Approach to Additive Harmony Music in France, 1889-1940," PhD dissertation, Yale University, 2013.

Alfredo Casella, “Ravel’s Harmony,”

The Musical Times 67, no. 996 (February 1, 1926): 124-27. (Cited by Blättler)

Charles-Simon Catel,

Traité d’harmonie (Paris, 1802). Digital facsimile published on the Internet Archive. Source: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Note: An edition from 1874 shows no changes in text or examples for the dominant ninth. Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France at gallica.bnf.fr.

Jeremy Day-O'Connell,

Pentatonicism from the Eighteenth Century to Debussy (2007).