In a previous post (Bauer, Part 1), I created a chordal reduction and wrote the following about the last bars of the B section, leading to the reprise:

"Also, the V7/ii itself [see the final bars in the graphic below] can be explained by separating out the left-hand elements in bar 17 [at the farthest right]. The first thing we hear is in fact ii—not V—as iiadd6; only on the third quarter beat is the bass G2 sounded. Although the overall effect here is certainly that of a break, the harmony does offer some continuity."

The device that the composer uses in this passage is firmly within late-19th and early-20th century practice. Recall that the notion of the identity of viiø7 as V9 without its root goes back to the 18th century. By the time we reach an era where the voicing of sonorities becomes an important factor, it is not surprising to see what we might call a "play of functions," grounded in perfect fifths. In the graphic below, (a) is the major dominant ninth chord with the two P5s bracketed; (a1) and (a2) depict what Bauer does in "Epitaph"--that is, briefly drop the root and thereby "expose" the upper fifth D-A. I have filled out the scheme with V9#11 at (b), and V13 at (c). At (b1) is the common diatonic -2 voicing of V11, which offers a third P5. By the time we reach (c), there are four P5s, and--theoretically at least--any of the upper ones could replace the lowest fifth. As an aside, (a3) and (c5) as quintal chords lose almost all the character of the traditional V9 and V13.

Because the relationship is diatonic (B minor to G major), this passage often appears in harmony textbooks. Johann Strauss, jr., does something similar in the transition--moving from Eb major to Ab major--out of the second into the third waltz in Frühlingsstimmen ("Voices of Spring"; second box below):

Appropriately for our blog, he gives strong expressive emphasis to V9 in the cadence (first box) and in the transition, too (second box again). The cadential V9 is very prominent in the vocal edition of this waltz set:

Here is a version with the tonic chord repositioned so that the strongly marked IV6/4 remains on the first beat:

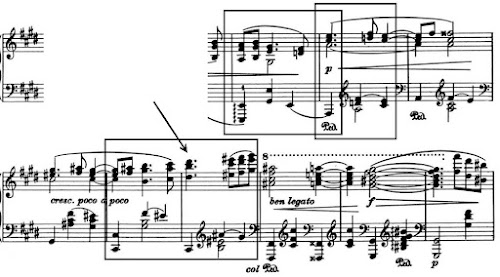

Given the presumed Impressionist influence on "The Epitaph of a Butterfly," it should be easy to locate examples of the "play of functions" in Debussy. Layering is of course a basic technique in his music, but as to using layers to suggest a change of function or modulation, my admittedly brief search has offered only this from the reprise in Reflets dans l'Eau ("Reflections in the Water"). A strongly defined Db: V9 (root and fifth circled) loses it root, perhaps by the second but certainly by the third bar, leaving eb7. The reverse process follows, as a b-flat minor triad is undergirded a couple bars later by a tonic fifth Db2-Ab2.