Harder/Steinke

In Harmonic Materials in Tonal Music, Pt. II, 6th ed., the three extended chords are grouped together, and the model of superimposed thirds is assumed. The historical summary I might have written myself: "Used sparingly by earlier composers, ninth, eleventh, and thirteenth chords occur more frequently toward the end of the 19th century. They are especially characteristic of Impressionistic music." The chords may be built on any scale degree, "but the majority are dominant chords."

The chords are definitely regarded as harmonies, but the authors acknowledge that "since these tones often appear as non-harmonic devices, it is sometimes difficult to decide whether they should be interpreted as members of the harmony or as incidental melodic occurrences." Given this quite reasonable statement it seems odd that they do not offer more repertoire examples--there is none with a direct resolution.

Hindemith

The laconic style of Traditional Harmony, vol. 1, was quite deliberate: the volume is really a set of exercises with notes for reference, not a narrative or expository presentation. Hindemith ignores third-stacking except for the dominant ninth chord. He does not mention 11ths, and the 13th originates from substitution; he says "dominant seventh chord with sixth"--which replaces the fifth--but figures the 6 as 13. He allows first and third inversions of the ninth chord, not the second or fourth (implicitly--he just doesn't mention them). Finally, he says that "in progressions, the two derivations [9th and 13th] and their inversions are treated like V7 and its corresponding inversions." The exercises maximize spelling opportunities and as such don't really reflect characteristic practices in existing compositional genres.

Ottman

In Advanced Harmony: Theory and Practice, 4th ed., ch. 10 is divided into three topical units: (1) "chords of the ninth," (2) "eleventh and thirteenth chords," and (3) exercises in "writing ninth chords" plus "the ninth chord in the harmonic sequence."

After an introduction, the sub-sections in the first unit are (1) "ninth chords in which the ninth resolves before a change of root," (2) "ninth chords in which the ninth resolves simultaneously with the chord change," (3) "ninth chords in which the ninth and seventh are arpeggiated," (4) "irregular resolution of the ninth," (5) "ninth chords in sequence." Third stacking is used, and non-dominant ninth chords are accepted but are only "occasionally seen."

Of the ten textbooks discussed in this series, Advanced Harmony has the best arrangement of well-defined sections coordinated with multiple repertoire examples.

Sub-sections 1 and 2 align with my "internal resolution" and "direct resolution" of the major dominant ninth chord. After noting that most internal resolutions can be regarded as melodic figures over V7, Ottman does observe that "When the ninth is held or repeated, a stronger feeling for an independent ninth chord may result. . . . As emphasis on the ninth increases, analysis as a ninth chord becomes more likely, but in any case, the decision is a subjective one at best." This aligns with my emphasis on a melodic-to-harmonic continuum in my "seven types" (link).

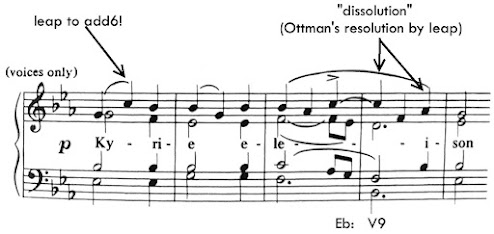

Sub-section 3: Here is the reference example with my annotations.

The one example in sub-section 4 is an upward resolution of the ninth, which should be very familiar to readers of this blog and my essays published on Texas ScholarWorks (see the index here: link). Sub-section 5 consists of a reference example showing alternating seventh and ninth chords in a sequential passage--the same progression from Mitchell's Elementary Harmony that I reproduced in the previous post.

Piston/Devoto

In Harmony, 5th ed., chs. 22 & 23 are on seventh chords other than the dominant seventh. Ch. 22 is short, more of a footnote to the preceding: it's on the "incomplete major ninth"--that is, to say the half-diminished seventh or viiø7. The idea that this chord may be added to below--"subtended"--goes back to Rameau and appears in many 19th century texts and treatises.

Ch. 24, then, takes up the ninth chord proper, which of course is called the "complete dominant ninth."

The author(s) isolate "three important aspects" of the chord:1. "The ninth may appear as a non-harmonic tone, resolving downward into the fifth degree [my internal resolution], or sometimes, if it is the major ninth, up to the seventh degree [my ascending figure], before the chord itself resolves. It is often an appoggiatura, in which case the harmonic color is very pronounced."

2. "The ninth may be used in a true harmonic sense as a chord tone but it may be absent from the chord at the moment of change. This is an important aspect of harmonic treatment of the ninth in common practice. It actually consists of the resolution by arpeggiation of a dissonant factor, a principle applied to no other dissonant chord (it is also called dissolution by some theorists). . . ." Ottman's 9-to-7 arpeggiation--see the musical example earlier in this post--is one instance of this.

3. "Finally, the ninth may act as a normal dissonant chord tone resolving to a tone of the following chord." This is my external or direct resolution.

The major dominant ninth has further limitations; it represents a harmonic color characteristic of the end of the common-practice period rather than the eighteenth century. Employed as in the third of the aspects just described, it is rarely encountered until the latter part of the nineteenth century. We will meet the dominant major ninth again in Part Two of this book in connection with impressionistic harmony, in which it is of great importance both as an independent, quasi-consonant sonority and as an adjunct to the triad in modal harmony.

Here is their particularly clear presentation of inversions, with my annotations. The fourth inversion (with ninth in the bass) is rejected.