The topic of section 2 is "Consonance/dissonance parallelisms and lines (mostly descending)."

Heading: ^8-^6.

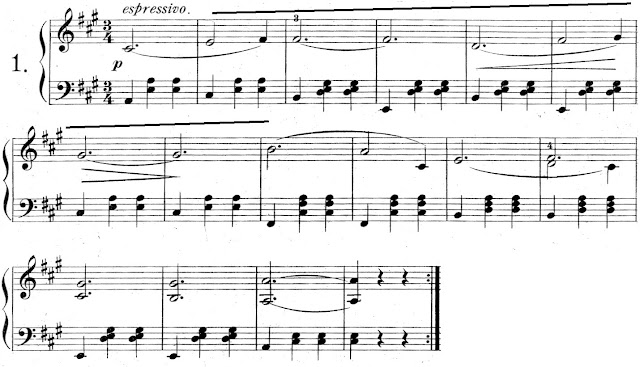

In the second number of Strauss's Italienischer Walzer, op. 407 (1882), between the tonic triad with ^8 in bar 1 and the V7 with ^5 on the last beat of bar 8 lies a series of remarkable dissonances: the relatively rare I7 (the arrow in bar 2 points to ^7), an unequivocal Iadd6 in bar 3, a I with #^5 against an "indifferent" accompaniment, and a prolonged V9 where ^6 "relaxes" into ^5 internally but at the last moment.

Italienischer Walzer, op. 407 (1882), no. 2

Adelen-Walzer, op. 424 (1886), no. 3b. Here is another I7, made all the more prominent by its hypermetric position. The dissonance is less daring than in the previous example, though, because B4 can be heard in retrospect as "passing" to Bb4 on the way to A4 over IV. The circled notes in bar 6 show a V9 where the ninth is internal--textbooks allowed such parallel sixth constructions (here A5-F6 to G5-E6). With the obvious anticipation of the tonic notes, we can fairly call this a direct resolution of V9.

Heading: line ^6 to ^3

Gartenlaube, op. 461 (1895), no. 3. we hear ^6-^5-^4 and briefly ^3 all over V. The register of ^3 (B5) is left open this way and we subsequently hear it over I when the 8-bar consequent starts up. Bar 12 = bar 4, but the register is immediately left open again, and this time it is picked up by the dramatic cadence chord, vii°7/V (circled).

Heading: line ^7-^3

From the beginning (no. 1, first strain) of the Italienischer Walzer, an indirect resolution of 7 (F5) to E5, so close and clear that it's the sort I like to call "almost direct." Note also that the full range of scale degrees over V is given (the bracket)—^7, ^6, ^5, and ^4.

Emile Waldteufel's Myosotis, op. 101 (1867), is a bit earlier than the late Strauss waltzes I have been discussing in this series. I have included it here to show that Strauss wasn't the only one to indulge in a delightful confusion of scale degrees and accompanying harmonies. The V9 resolution is direct (bars 6-7).

Heading: ^4-^1 (or farther)

Again Strauss: Hochzeitsreigen, op. 453 (1893), no. 2. The pre-dominant or subdominant-function harmony is given unusual prominence, and ^6 acts traditionally as a suspension dissonance (G5 in bars 1-2). As the melody continues down, past ^1, the 8-bar antecedent ends with an "almost direct" resolution of the ninth to ^6 in a Iadd6 harmony. Note also the ninth in V9/V as a cadence accent in bar 15 (not marked). As a point of interest—no V9 involved—I have also shown the waltz's final 8-bar consequent with its tonic ending. The overall design is 16 bar antecedent (itself a period--shown below--then 16 bar consequent, of which the final bars (or 25-32) are shown below.

Tchaikovsky, The Nutcracker (1892), Waltz of the Flowers. The confusion of scale degrees and their harmonies that we saw in Waldteufel's Myosotis is even greater in the second strain of the Waltz of the Flowers. In the antecedent phrase: the F#5 in bar 1 is fine, but what is C#5 exactly? What is E5? B4? D5? Things are just slightly better in the consequent phrase: G5, D5 and the subsequent quarter notes C#5 and A4, but what about F#5 and E5? A wonderful example of the freedom of treatment of melody in relation to harmony that Jeremy Day-O'Connell points out (in connection with a history of ^6), as also have Peter van der Merwe, Derek Scott, and Norbert Linke (I hope to complete an essay on their work before too much longer).

Heading: ^10-^7

Once again to Strauss: Kaiser-Walzer, op. 437 (1889), no. 3. I have remarked in earlier essays on the tendency to expand theme lengths in waltzes from the most conventional eight bars early in the 19th century (most of Schubert's, for example, but also early Lanner) to sixteen (late Schubert, Strauss, sr.) to thirty-two (Strauss, jr., and contemporaries). The most common design is effectively a 16-bar theme with two endings, where the repetition, with its second ending, is written out--see Hochzeitsreigen, no. 2, above for an example. In the Emperor Waltz, however, Strauss writes what I would call a true 32-bar period, where the two halves of the antecedent, bars 1-8 & 9-16, form a 16-bar sentence or antecedent-contrasting phrase. In that way, the distinctive opening of the antecedent doesn't return until bar 17 and the large design is clearly defined. I marked several things: at (a1) a line down from ^3 to ^7 (E6 to B5); at (a2)--the bracket--the considerable expansion of V with a ninth prominent in both color and position; at (a2)--box--and the arrow, C: V9 becomes G: V9 in the parallel position in the phrase; at (b), the theme closes in a quite conventional way.

Heading: Ascending

And, finally, to Waldteufel, Les Patineurs (1882), no. 1, the Skaters Waltz that is at least as famous as the Waltz of the Flowers and the Emperor Waltz. Here again the freedom of the scale degrees is remarkable, but now the motion is ascending and if anything the confusion of melody and accompaniment is greater. A brief hint of Iadd6 (bar 2) comes from ^6 anticipating its role as 9 in V9 (bars 3-4). The F#4 is still there over V in bar 6, but in the phrase parallelism it actually moves up, not down as we would expect in a resolution. It's not impossible to hear the G#4 as "resolving" to A4, but (1) it's interrupted by an expressive upper neighbor B4, and (2) the resolution is of melodic direction, not harmonic function. At the end, as a point of interest, I have included the second cornet's ascending line that is rarely heard over the melody in performance (F#4-G#4-A4).